In 2019, the Digital News Report looked at how young people get their news,1 finding stark differences in news consumption and behaviours among younger people, including a greater reliance on digital and social media and a weaker identification with and loyalty to news brands compared with older groups. Three years later, we now turn our attention to how young people’s news habits and attitudes have changed amid rising concerns about news distrust and avoidance, increasing public attention to social issues such as climate change and social justice, and the growth of newer platforms such as TikTok and Telegram.

In 2019, the Digital News Report looked at how young people get their news,1 finding stark differences in news consumption and behaviours among younger people, including a greater reliance on digital and social media and a weaker identification with and loyalty to news brands compared with older groups. Three years later, we now turn our attention to how young people’s news habits and attitudes have changed amid rising concerns about news distrust and avoidance, increasing public attention to social issues such as climate change and social justice, and the growth of newer platforms such as TikTok and Telegram.

Here, we aim to unpack these new behaviours as well as to dismantle some broad narratives of ‘young people’. Instead, we consider how social natives (18–24s) – who largely grew up in the world of the social, participatory web – differ meaningfully from digital natives (25–34s) – who largely grew up in the information age but before the rise of social networks – when it comes to news access, formats, and attitudes.2 These groups are critical audiences for publishers and journalists around the world, and for the sustainability of the news, but are increasingly hard to reach and may require different strategies to engage them.

In this chapter, we supplement our survey data with quotes drawn from qualitative research conducted by the market research agency Craft with 72 young people (aged 18–30) in Brazil, the UK, and the US.

The role of social media in young people’s news behaviours

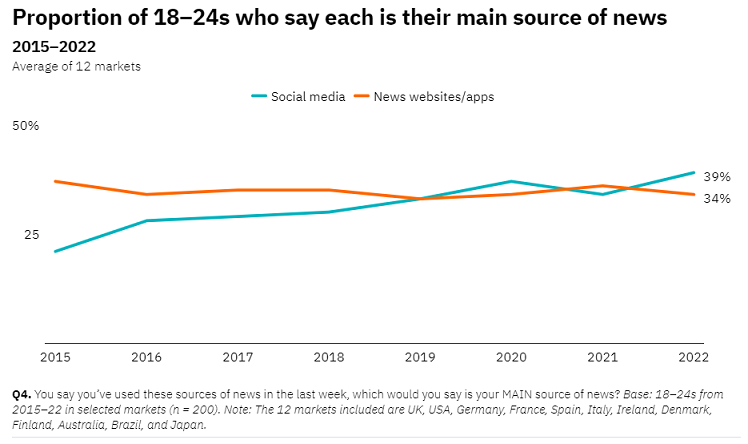

Since the Digital News Report began tracking respondents’ main source of news, social networks have steadily replaced news websites as a primary source for younger audiences overall, with 39% of social natives (18–24s) across 12 markets now using social media as their main source of news, compared with 34% who prefer to go direct to a news website or app. We also find that social natives are far more likely to access news using ‘side-door’ sources such as social media, aggregator sites, and search engines than older groups.

The social media landscape continues to evolve dramatically, with new social networks like TikTok entering the field as well as existing platforms like Instagram and Telegram gaining markedly in popularity among young audiences. As social natives shift their attention away from Facebook (or in many cases never really start using it), more visually focused platforms such as Instagram, TikTok, and YouTube have become increasingly popular for news among this group. Use of TikTok for news has increased fivefold among 18–24s across all markets over just three years, from 3% in 2020 to 15% in 2022, while YouTube is increasingly popular among young people in Eastern Europe, Asia-Pacific, and Latin America.

And while 25–34s have largely embraced many of the same networks as social natives in their daily lives and news habits, they have remained much more loyal to Facebook (9pp higher for news than social natives) – the network this cohort largely grew up with – and have been slower to move to new networks like TikTok (5pp lower for news than social natives).

What makes these networks so appealing to some younger audiences? Qualitative interviews reveal that they are drawn to the informal, entertaining style of visual media (and particularly online video) platforms – describing it as more personalised and diverse than TV, as a resource for rapidly changing events such as the Russia–Ukraine conflict, and as a venue for niche interests, from pop culture to travel to health and well-being.

On TV we always see the same things, but on YouTube, Spotify, TikTok, we have a range of diversity. … We can get all this and see that there is diversity, society far beyond just what we live.

Male, 18, Brazil

I find [YouTube] more digestible than mainstream media. I also find YouTube to be more interesting because it is more specifically geared towards me.

Male, 23, USA

However, the popularity of online video does not mean text- and audio-based formats don’t still have a big role to play in young people’s news habits. Under 35s still largely say they prefer to mostly read (58%) rather than mostly watch (15%) news – particularly, as our qualitative research finds, when looking for live updates and summaries or when keeping up with what is happening on a ‘need to know’ basis. Some say they seek out a mix of text and video content to better understand information. Others, particularly in Asia-Pacific and Latin American markets, are drawn to audio-based formats like podcasts that allow users to multitask while they listen. There is not a one-size-fits-all approach or medium through which newsrooms can attract younger audiences.

Why younger audiences avoid news

And yet, as more news outlets and formats compete for audiences’ time and attention, we continue to see longer-term falls in interest and trust in news across age groups and markets – particularly among younger audiences. Under 35s are the lowest-trusting age groups, with only a third (37%) of both 18–24s and 25–34s across all markets saying they trust most news most of the time, compared with nearly half of those 55 and older (47%). Young people also increasingly choose to avoid the news, with substantial rises in avoidance among social natives since we last asked this question in 2019. Across all markets, around four in ten under 35s often or sometimes avoid the news now, compared with a third (36%) of those 35 and older.

Why is this happening? Most often, younger audiences (under 35) say the news has a negative effect on their mood (34%) and, most recently, that there is too much news coverage of topics like politics or Coronavirus (39%). In particular, the longstanding criticism of the depressing or overwhelming nature of news persists among young people. For instance, in the UK, two-thirds (64%) of news avoiders under 35 say the news brings down their mood. Our qualitative research participants described forming habits of avoiding this negativity.

I tend to try and limit the amount of negative news I consume, especially first thing in the morning and last thing at night. I don’t want it to affect my day or make me worry.

Female, 29, UK

Depending on my mood, if I see news that I know is bad, is going to upset me, sometimes I leave it and read it later.

Male, 24, Brazil

Young people, particularly digital natives (27%), also at times avoid the news because they perceive it as biased or untrustworthy. As under 35s grew up in the digital age and have been socialised by older generations to be critical of the information they consume, our qualitative research suggests they take a particularly sceptical approach to all information and often question the ‘agenda’ of purveyors of news. In this sense, mainstream news brands are not inherently more valued for impartiality by some young people, and their wariness of bias at times pushes them away from consuming news altogether.

I do not think anything is 100% reliable in the mainstream media. You can never think that that is the absolute truth, because we are not sure of anything.

Female, 24, Brazil

A lot of the time, mainstream news can be very biased or politically motivated. This makes it hard to decipher its credibility.

Female, 28, USA

Yet many young people are not necessarily avoiding all news. In fact, many of them are selectively avoiding topics like politics and the Coronavirus specifically. As the Executive Summary notes, these patterns of selective news avoidance are not limited to younger audiences. But our qualitative research suggests that, among these groups, perceptions of political news are intrinsically tied to other themes of news avoidance: beliefs that it is particularly negative, that there is nothing they can do with the information, or that it is less trustworthy than other forms of news. Rather than simply avoiding news, there is ‘news to be avoided’.

I actively avoid news about politics as it frustrates me. It makes me feel small and no matter what my views it won’t make any difference at all to what goes on in the country or world, so there is no point listening to it.

Female, 22, UK

On days where I really want to relax, I avoid political news because it gets me anxious sometimes.

Female, 24, USA

What is news to young people?

These perceptions of too much newsroom attention going towards topics like politics and Coronavirus also reflect younger audiences’ broader desire for diverse news agendas, voices, and perspectives. As we discuss throughout this report, young people – particularly 18–24s – have different attitudes toward how the news is practised: they are more likely than older groups to believe media organisations should take a stand on issues like climate change and to think journalists should be free to express their personal views on social media.

On top of that, many young people have a wider definition of what news is. As our qualitative research reveals, younger audiences often distinguish between ‘the news’ as the narrow, traditional agenda of politics and current affairs and ‘news’ as a much wider umbrella encompassing topics like sports, entertainment, celebrity gossip, culture, and science. This is reflected, for instance, in the examples of ‘news’ our interview participants shared: from stories about the world’s biggest strawberry to pollution on local beaches to the latest episode of Big Brother.

Given that young people are generally less interested in news and access it less frequently than older audiences, it is not surprising that under 35s express lower interest in most news topics generally. But they are particularly less likely to be interested in what they consider to be ‘the news’ – traditional beats like politics, international, and crime news – and tend to be less inclined to consume Coronavirus coverage. Instead, under 35s are more likely to be interested in ‘softer’ news topics: entertainment and celebrity news (33% interested), culture and arts news (37%), and education news (34%).

I like news about sports, food, well-being, and health. I don’t like seeing news about violence.

Male, 27, Brazil

Even many of the types of news often deemed ‘young’ topics – for instance, mental health and wellness, environment and climate change news, and fun news or satire – do not necessarily translate into greater interest among all young people across all markets (or at least, interest in news, specifically, about these topics). Younger audiences on average don’t have much higher interest than older audiences in news on social justice issues, for instance, though this interest varies dramatically by market. Interest in social justice news is nine percentage points higher among under 35s than those 35 and older in the UK, on a par across both groups in Brazil, and seven percentage points lower among under 35s in Germany. As we discuss in a later section, those 35 and older are also more likely than younger people to say they are interested in environment and climate change news.

Motivations to access news

This year, we also asked about why people personally choose to keep up with the news. All age groups see the news as equally important for learning new things, but news users under 35 are slightly more motivated than older groups by how entertaining the news is and how sharable it is, and they are slightly less motivated than older groups by a sense of duty to stay informed of news or by its personal usefulness to them.

However, the extent to which young people feel a sense of duty to consume news looks very different across countries – for instance, with huge gaps between those under versus over 35 in Brazil and the US but very small gaps by age in France and Japan. And in the UK, a sense of duty to be informed and feeling the news helps them learn new things are tied for the top motivation for consuming news among under 35s. Together with insights from our qualitative research, this suggests that young audiences engage in a sort of mix-and-match of motivations depending on their interests as well as the types of content they are thinking of or seeking out.

I access the news partially for fun and partially for entertainment but also to be informed. There are also science magazines, where it’s not fun, but it’s not ‘need to know’ either.

Female, 23, USA

I am looking for what I need to know to stay relevant with current events … That news is important and relevant to my life. Also, I look for news that is going to entertain my personal interests and fun news that is exciting to discover such as current celebrity news.

Male, 27, USA

Conclusions

As the digital media environment rapidly evolves and more young adults who grew up with social media enter our sample, key differences among younger news audiences continue to crystallise. The point here is not simply that some of young people’s behaviours and preferences are different from those of older people. They long have been. It is that the differences seem to be growing, even between social natives and digital natives. Many of these shifts in behaviours are so fundamental that they appear unlikely to be reversed with time. The youngest cohort represents a more casual, less loyal news user. Social natives’ reliance on social media and weak connection with brands make it harder for media organisations to attract and engage them.

At the same time, younger audiences are also particularly suspicious and less trusting of all information. This, along with the often-depressing nature of news and the overwhelming amount of information they encounter in their daily lives, makes young people sceptical of news organisations’ agendas and increasingly likely to avoid the news – or at least certain types of news. While young people do not all have the same needs, many are looking for more diverse voices and perspectives and for stories that don’t depress and upset them.

Social natives in particular have increasingly moved towards new visual social networks – but they are not simply all TikTokers, nor do they all have limited attention spans when it comes to serious information. Young people like a range of formats and media, from text to video to audio, and are drawn to information that is curated for them. There will continue to be a place for text, video, audio, and still imagery – sometimes all in one piece of content. And there will be a place for both the serious, impartial tones of traditional media and more casual, entertaining, or advocacy-centred approaches to covering news.

Younger audiences’ definitions of what news is are also wider. Recognising the variety of preferences and tastes that exist within an incredibly diverse cohort presents a new set of challenges for media organisations. But one route to increased relevance for news brands may lie in broadening their appeal – connecting with the topics young people care about, developing multimedia and platform-specific content, and aligning content and tone with format – rather than entirely replacing what they already do or expecting young people to eventually come around to what has always been done. At times, this includes continuing with what news brands currently offer, some of which is highly valued by younger audiences. In moments when they feel they ‘need to know’ what is happening – as with COVID-19 and the Russia–Ukraine conflict – young people still want news brands to be there.

Written by Dr Kirsten Eddy at Reuters Institute