Indian media are extremely diverse, with thousands of outlets operating in multiple languages. Much of the media is controlled by large, for-profit corporations, many of them privately held, and mainly funded by advertising. But these business models are being disrupted by a rapid shift to online consumption – and the impact of COVID-19.

Indian media are extremely diverse, with thousands of outlets operating in multiple languages. Much of the media is controlled by large, for-profit corporations, many of them privately held, and mainly funded by advertising. But these business models are being disrupted by a rapid shift to online consumption – and the impact of COVID-19.

Legacy print news brands, including the most popular in the survey – Times of India, Hindustan Times, and The Hindu – and newspapers in general, have borne the brunt of the slowdown. The pandemic has hit print circulation and decreased advertisements, leading companies to slash salaries, cut jobs, and close editions across the country due to the drastic decline in economic activity in one of the world’s strictest lockdowns.1 The industry has also had to cope with reduced government and commercial advertisement spending, which fell by more than half since the start of the pandemic. Leading news channel NDTV announced salary cuts for a time, while digital born-operator The Quint furloughed staff and was forced to close its planned TV division after three years’ unsuccessful attempts to get a broadcasting licence.

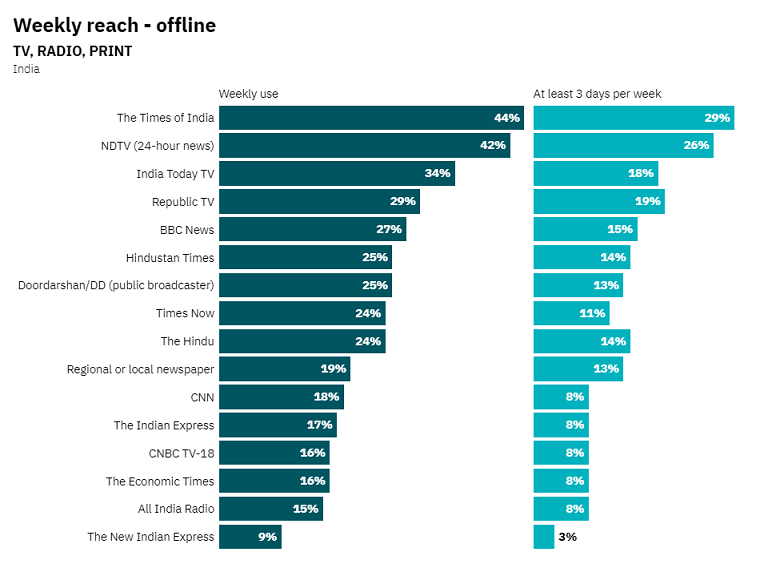

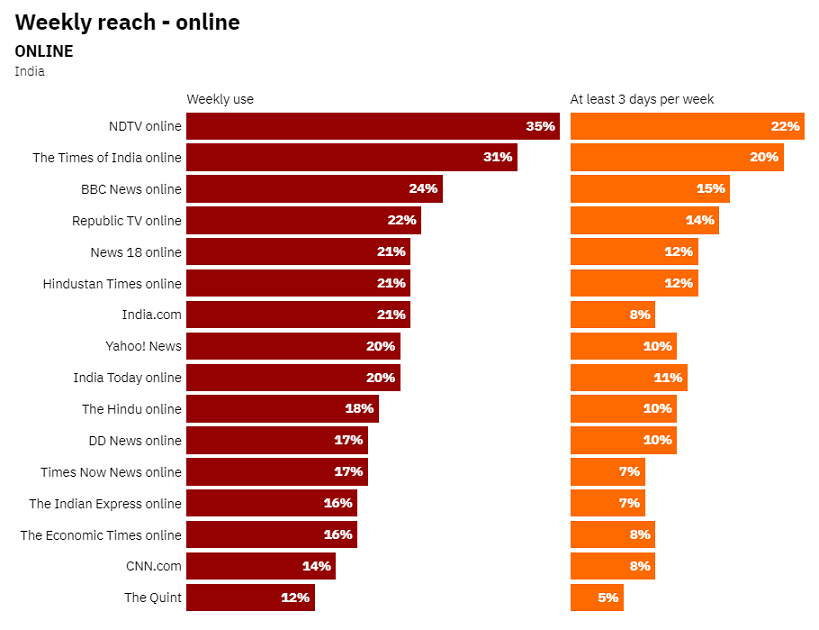

Despite the growing popularity of digital media with our surveyed audience, which tends to lean towards an urban and educated population, television remains the most popular source overall. India has altogether 392 news channels, dominated by regional language channels and private players. Broadcast television channels, like print media in India, are self-regulated and often have strong political affiliations and corporate ownership, with no regulations on cross-media ownership. A culture of 24×7 news channels operating on ‘Breaking news’ models and polarised debates often distort and sensationalise news.

In October last year, news channels faced a credibility crisis as their Television Rating Points (TRPs) published by the Broadcast Audience Research Council (BARC) came under scrutiny. Republic TV and two Marathi entertainment channels were accused by the Mumbai police of tampering with metering devices installed in selected sample households to boost their ratings. Despite these accusations, the considerable popularity enjoyed by Republic TV’s online and offline platforms – which have both increased considerably since our last survey in 2019 – perhaps indicate the growing popularity of right-wing ideology propagated by the ruling party in India.

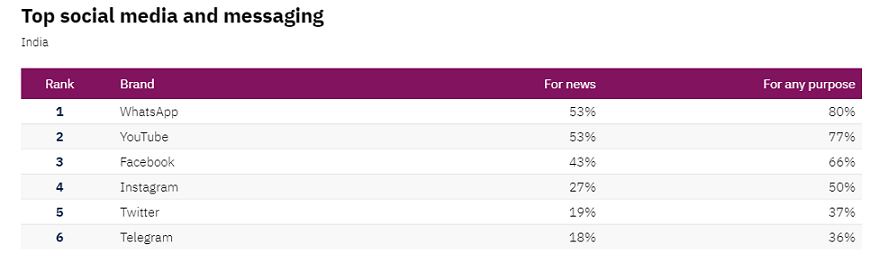

India is one of the strongest mobile-focused markets in our global survey, with 73% accessing news through smartphones and just 37% via computer. India has more than 600 million active internet users, many of whom access the internet only through mobile phones – aided by low data charges and cheap devices.

Among our respondents, WhatsApp, YouTube, and Facebook are widely used for news and there have been serious problems with misinformation and hate speech. Individual members of the ruling BJP and groups aligned with the party are alleged to systematically spread false and misleading information via social media and other platforms.2 In late 2020, Facebook India’s policy head resigned after accusations that the company deliberately took a lenient line on ruling party supporters who allegedly violated hate speech rules with anti-Muslim posts.3 In response, the number of independent fact-checking organisations has grown in recent years, with support from international tech companies and foundations, while mainstream media organisations have formed dedicated fact-checking and debunking teams.

With the growing popularity of online platforms, the Indian government has come up with controversial new proposals to expand the scope of existing legislation to social platforms, news websites, and Over the Top (OTT) content providers. In an apparent step to limit false and objectionable information on social media platforms, new guidelines expect platforms to trace the origin of information that can be misleading or objectionable based on an order from a court or competent authority. Authorities have on several occasions asked platform companies to block posts, including those by activists, journalists, and opposition politicians.

DigiPub, a group of digital news organisations formed in 2020, says these rules go against the ‘fundamental principles of news’, giving control to the government to remove news content online. India has consistently slipped in the Press Freedom Index of Reporters Without Borders in the last few years, occupying 142nd position out of 180 countries.4 RSF’s 2021 report notes journalists in India face increasing violence, trolling, and threats of rape and death on social media, along with excessive use of sedition laws for criticism of the government or its policies. Freedom House changed India’s status from ‘free’ to a ‘partly free’ country earlier this year.

Methodology note

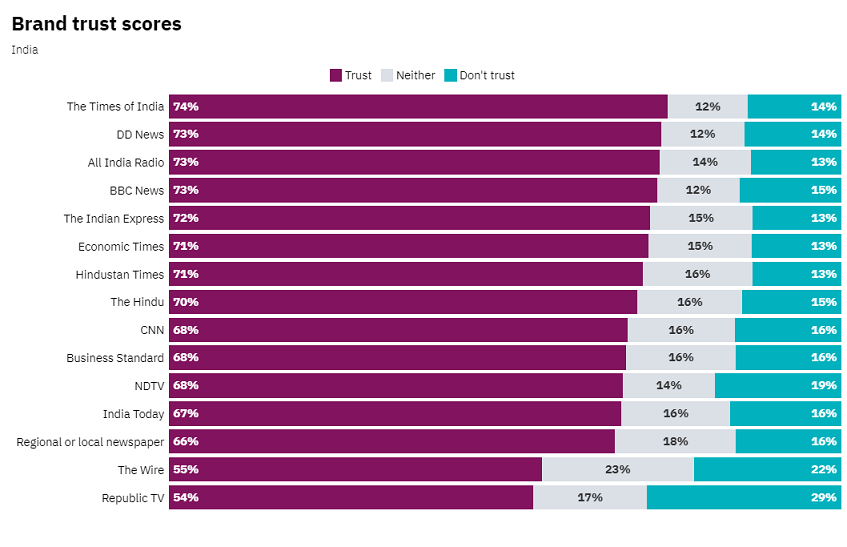

These data are based on a survey of mainly English-speaking, online news users in India – a small subset of a larger, more diverse, media market. Respondents are generally more affluent, younger, have higher levels of formal education, and are more likely to live in cities than the wider Indian population. Findings should not be taken to be nationallyLegacy print brands and government broadcasters, DD News (Doordarshan) and All India Radio, retain high levels of trust among consumers. Print brands, in general, are more trusted than television brands, which are far more polarised and sensational in their coverage. Republic TV, despite its popularity as a news source, has lower trust scores than legacy print and television brands – and the highest levels of distrust.

Written by Anjana Krishnan,Research Associate, Asian College of Journalism, Chennai

Source:Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism