Old habits are a powerful yet overlooked driver of consumer resistance to new products.

Old habits are a powerful yet overlooked driver of consumer resistance to new products.

It’s hard enough to persuade consumers to buy a new product. But after they buy it, they need to adopt it, which, it turns out, is a major hurdle. Consumer resistance comes in many shapes, and the power of old habits is an oft-underestimated foe. Understanding the phenomenon can prevent a firm’s R&D efforts from winding up on the vast trash heap of failed innovation.

What consumers intend to do and what they actually do are two separate affairs. At some point, most of us have bought an item with every intention to use it and yet failed to do so. Maybe it was a bottle of multivitamins, a new perfume or an ab exercise wheel, a classic example if there ever was one.

Most mechanisms of resistance are active, i.e. consumers make an explicit decision not to adopt a product because of some concern. However, Jennifer Labrecque of the University of Southern California and I, along with non-academic partners, conducted research to examine a form of passive resistance we call habit slips – when consumers fail to adopt a new product by sheer force of habit.

The most common reason for non-adoption

In our paper, published in the Journal of the Academy of Marketing Sciences, we show that unintentionally slipping back into old habits is the most common reason why consumers rarely use a new product despite their best intentions. However, we also find that marketers can promote the use of a new product by encouraging consumers to integrate it into their existing routines. In short, habit is a powerful force that marketers should leverage, not fight.

We began our investigation with a survey. A set of 150 participants, recruited on MTurk, named two products that they had purchased in the last six months, identifying one that they used regularly and one that they had intended to use regularly but didn’t. They nominated a wide array of products, ranging from electronics to household supplies.

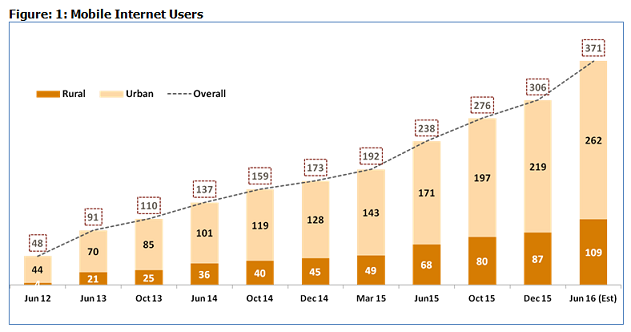

Participants were asked to choose one of 13 possible reasons why they rarely used the product they had bought. The most common answer, accounting for a quarter of participants, was: “I fell back on my old habit and did what I used to do.”Figure 1 lists the top five reasons

Another of our survey findings was that 63 percent of participants said the regularly used products replaced an item that was already embedded in routines. Only 25 percent indicated that the rarely used products had found such a built-in slot in their lives. To illustrate this, think of tofu and soy milk adoption in the United States. Tofu has been produced in the U.S. since 1878, more than a century before soy milk (1985). However, soy milk gained ground much faster, due in no small part to the fact that people could readily use it as a milk substitute. Tofu had no such “luck”. Lacking a clear staple equivalent, it had to carve itself a place in the food habits of Americans.

Piggybacking on existing routines

After the survey, we ran an experiment to evaluate the mechanisms behind habit slips and two specific strategies to overcome them. In this study, 70 college students, split into three groups, trialled a fabric refresher, a laundry product that was new and conflicted with their established habits. They could easily slip back into old laundry habits.

The first group was simply told to use the product on clothes they had already worn but wanted to wear again.

The second group received the same basic instructions but were also asked to specify when, where and how they would use the fabric refresher, e.g. “When I get dressed in the morning, I’ll do a sniff test on the item I want to wear again. If it’s smelly, then I’ll use the fabric refresher.” This “if-then” strategy was meant to promote the use of the product by creating a behavioural trigger. However, it also involved forming a habit where there was none.

Like all other participants, the third group received the basic instructions, but were also instructed to use the fabric refresher as a direct substitute to their existing laundry habit, i.e. whatever they usually did with previously worn clothes they wished to wear again. For example, if the student usually washed her dirty jeans (or alternatively: just grabbed them off the floor before running to class), she was to stop and think: “Don’t do what you normally do. Use the fabric refresher instead.”

Habit slips are like glitches in behaviour

As anticipated, participants from the third group were the most successful at using the new laundry product as they tied it to their existing habit. They used the fabric refresher 19 percent more often than the control group (13.28 vs 11.17 times over four weeks). Usage in the second group (“if-then”) was similar to the control group.

We also confirmed that study participants with strong, clear-cut laundry habits tended to fall back on their usual routine, regardless of their intention to use the new product and their positive evaluation of it. Habit slips are akin to glitches in the rational control of behaviour. Even when consumers fully intend to use a new product they like, old habits get in the way.

Finally, we found that participants were especially likely to fail to use the new product when they didn’t give much thought to their laundry. Not paying attention made it all the easier for them to mindlessly revert to old habits.

What’s a marketer to do?

Although new products and services might appear desirable in the abstract, those that conflict with existing habits are unlikely to be used. Our research indicates the importance of studying barriers to adoption within the context of consumers’ daily lives. This could take the form of ethnographic research (i.e. observing people as they use a product in their own environment) and other types of naturalistic experiments. Consumer reports on actual product use could also prove to be useful.

Instead of fighting consumer habits, marketers should think of ways to leverage them. They could consider, for instance, strategies such as habit stacking, also called piggybacking. In the domain of behaviour change, there is no one-size-fits-all, however. It’s about finding the right fit between a product and the relevant, actual habits of specific consumers.

A lot could be done also in terms of packaging or product design. Successful examples include sweeteners sold in easy-to-carry sachets, nylon shopping bags that fold in a pocket-size format and stationary bikes with earphone jacks and screens for people to watch their favourite TV shows as they exercise.

Fact: Over half of all new products fail. Marketers would do well not to underestimate the role of habits in this sobering statistic, and take heart that a former foe can be turned into a friend.

Written by Wendy Wood,Provost Professor of Psychology and Business at the University of Southern California. From January 2018, she will be the Distinguished Visiting Chair of the INSEAD-Sorbonne University Behavioural Lab.

This article is republished courtesy of INSEAD Knowledge. Copyright INSEAD 2017